As the internet continues to evolve, new cyber threats are constantly emerging. Without proper protection, websites are vulnerable to attacks that can cause significant damage. That’s why it’s crucial to invest in top web security tools to enhance the safety of your website.

Understanding Web Security and its Significance

Web security refers to the practices and techniques used to protect websites from cyber threats and attacks. As the internet continues to evolve, so do the risks associated with website security. Hackers and cybercriminals are constantly developing new methods to exploit website vulnerabilities, making it essential for website owners to stay one step ahead with robust security measures.

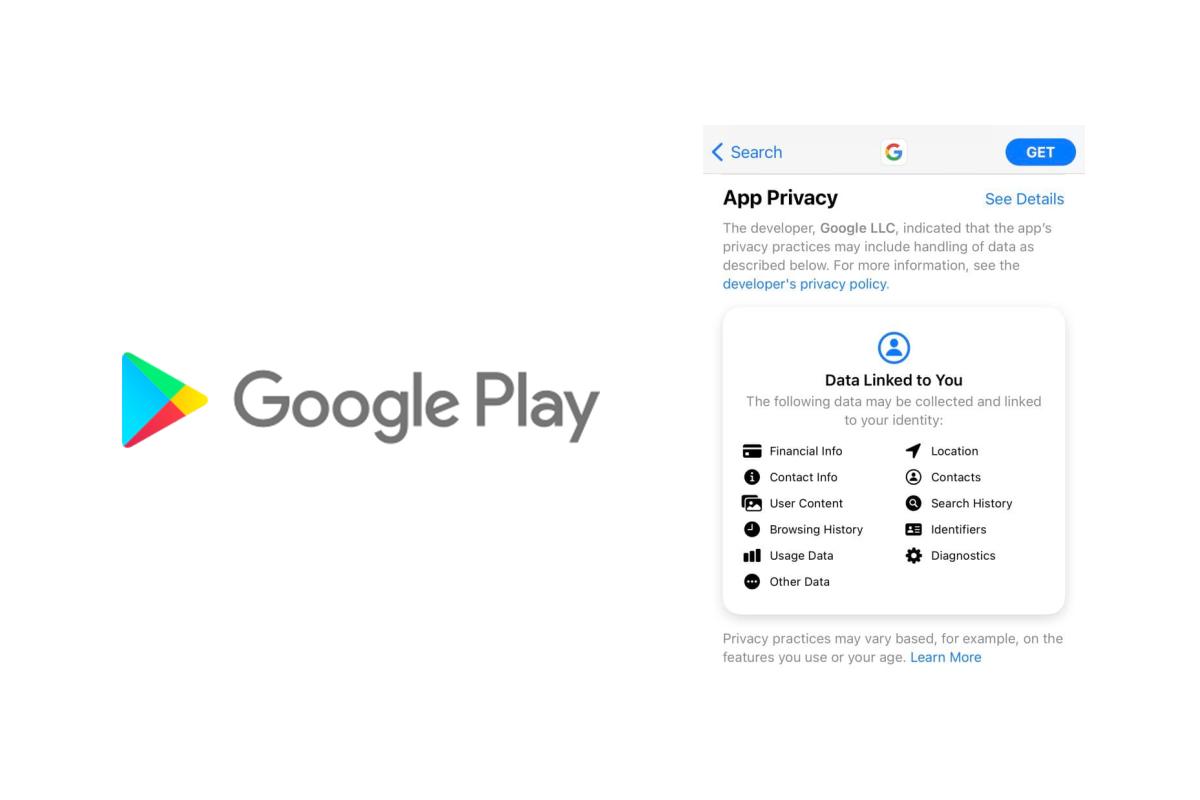

Website security is crucial for several reasons. Firstly, a security breach can result in the theft of sensitive and confidential information, including personal data and financial information. This can damage a company’s reputation and lead to legal and financial repercussions. Secondly, a security breach can disrupt website availability and compromise its functionality, leading to lost revenue and a negative user experience. Lastly, website security is essential for maintaining compliance with industry regulations and standards.

Web Application Firewalls: Protecting Your Website Against Attacks

If you’re running a website, it’s crucial to protect it from cyber threats. One way to do this is by using a web application firewall (WAF). A WAF is a security tool that filters and monitors traffic between a website and the internet, inspecting all incoming data to identify and block potential attacks.

WAFs are designed to protect against various types of attacks, including SQL injection, cross-site scripting (XSS), and distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks. By blocking these attacks before they reach the website, WAFs can help prevent data breaches, defacements, and other security incidents that can harm a website’s reputation.

How Web Application Firewalls Work

A web application firewall works by analyzing the contents of each HTTP request and response to and from a website. It uses a set of rules to determine if the traffic is legitimate or not.

For example, if a WAF detects a request that matches a known SQL injection pattern, it will block that request and prevent the attack from succeeding. Similarly, if a WAF detects an HTTP response that contains malicious content, it can block that response as well. WAFs can be deployed as hardware devices or software applications, and they can be hosted on-premises or in the cloud. Some WAFs are also available as a service, which makes them easy to deploy and manage.

Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) Certificates: Encrypting Data for Secure Communication

When it comes to website security, one of the most important tools in your arsenal is the Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) certificate. SSL certificates encrypt data transmitted between websites and users, ensuring that sensitive information, such as login credentials and payment details, cannot be intercepted by hackers.

Having an SSL certificate installed on your website also provides an extra layer of security and reassures visitors that their information is safe. In fact, many browsers now display a “Not Secure” warning for websites that do not have an SSL certificate installed. Obtaining an SSL certificate is relatively easy and can be done through your web hosting provider or a third-party certificate authority. There are several types of SSL certificates available, including Domain Validated (DV), Organization Validated (OV), and Extended Validation (EV) certificates, each providing varying levels of verification and security.

Two-Factor Authentication: Adding an Extra Layer of Protection

In today’s digital world, usernames and passwords are no longer enough to secure your website. Hackers use various tactics like phishing, social engineering, and brute-force attacks to gain unauthorized access. This is where two-factor authentication (2FA) comes into play. 2FA adds an extra layer of security to your website login process, making it difficult for attackers to take over your website.

With 2FA, users have to provide two forms of identification to access their accounts. In addition to the usual username and password, they’ll have to enter a code that’s usually sent to their phone or generated by an app. This means that even if a hacker gets hold of your username and password, they still won’t be able to access your account without the additional form of identification. It offers a simple and effective way to protect your website against unauthorized access. It’s easy to set up and adds an extra layer of security without adding too much complexity to the login process. By implementing 2FA, you can ensure that your website remains safe and secure.

How to enable 2FA for your website?

Enabling 2FA for your website is a simple process. You can either use a plugin or a third-party service to set it up. There are many 2FA plugins available for popular content management systems like WordPress and Drupal. You can also use a third-party service like Google Authenticator or Authy.

Once you’ve installed the 2FA plugin or signed up for the third-party service, you’ll need to enable it for your website’s login process. This usually involves configuring a few settings and adding a code to your login page. Once you’ve done this, users will be prompted to enter their two forms of identification every time they log in.

It’s important to note that 2FA is not foolproof and can be bypassed in certain situations. However, it’s still a great way to add an extra layer of security to your website and protect it against most attacks.

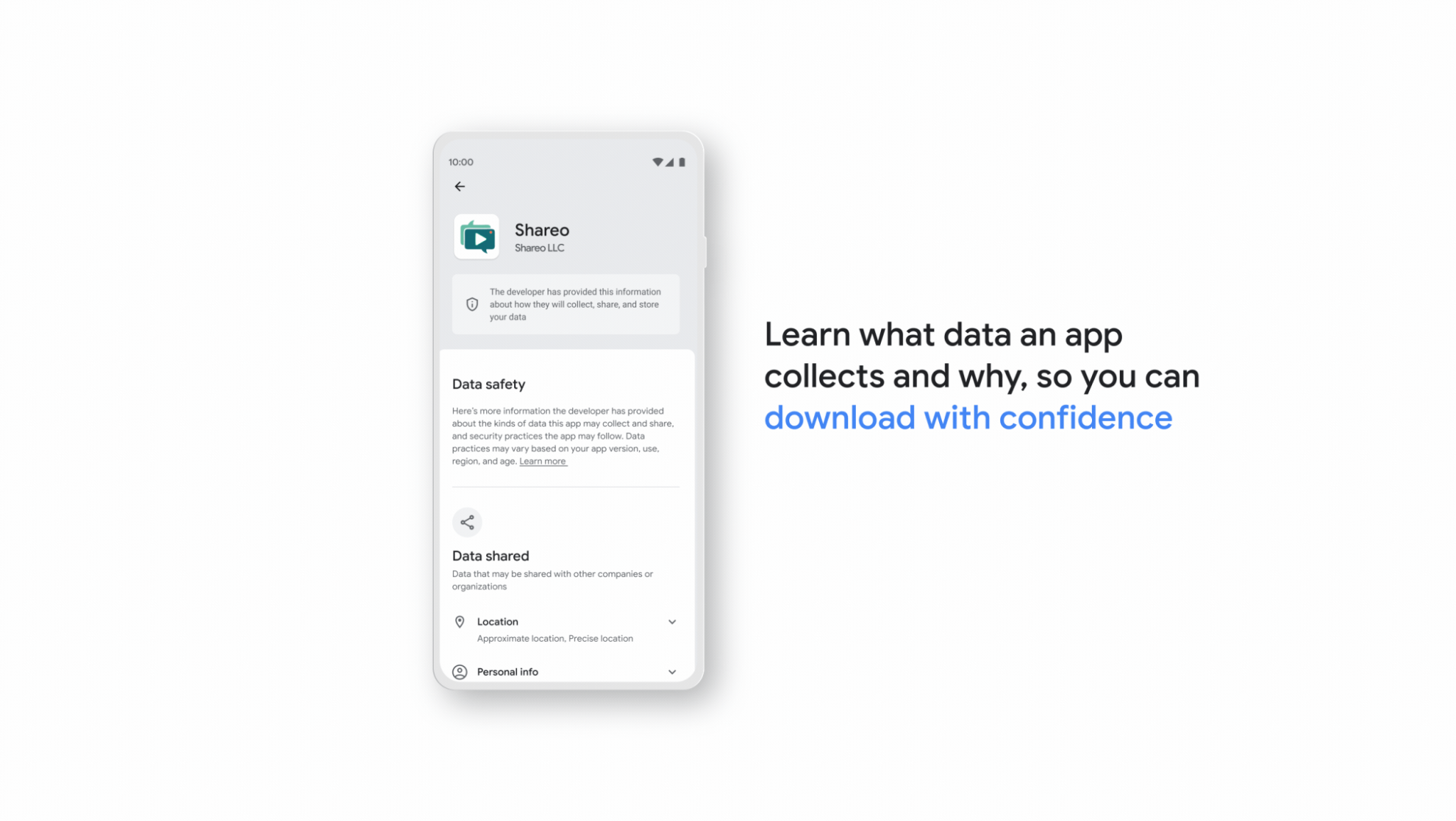

Security Plugins: Enhancing Website Security with Add-Ons

As cyber threats become more sophisticated, it is essential to take proactive measures to safeguard your website. Along with web application firewalls (WAFs), SSL certificates, two-factor authentication (2FA), vulnerability scanners, content security policies (CSPs), and intrusion detection systems (IDS), security plugins can add an extra layer of protection to your website.

Popular Security Plugins

Wordfence Security: One of the most downloaded security plugins for WordPress, Wordfence offers features such as malware scanning, firewall protection, and login security to protect your website.

Sucuri Security: A comprehensive security plugin that offers a website firewall, malware scanning, brute force attack protection, and even a content delivery network (CDN) to speed up your website.

Jetpack Security: This plugin offers a suite of security features such as real-time backups, spam protection, and malware scanning. It also provides downtime monitoring and resolution services.

While these security plugins offer valuable protection, it’s important to note that they are not foolproof. It’s still essential to follow best practices such as regularly updating your website software, using strong passwords, and avoiding suspicious links and downloads.

Wrapping Up

In conclusion, website security is an essential part of any online presence. By implementing the right security measures, you can help to protect your website from cyber threats and keep your visitors’ data safe. By following these best practices, you can help to keep your website safe and secure. Remember, security is an ongoing process, and staying vigilant is key to safeguarding your website from cyber threats.

Tags: Development, Jetpack, security development, Sucuri, Web, web security, Wordfence